Let's Get Rekt by VMProtect 3.8.1 with 100% Complexity

Introduction

Virtualization stands as one of the most formidable protection techniques, widely employed by both legitimate and malicious applications. I’ve been totally hooked on it especially since understanding VMProtect has become paramount in 2024 for reverse engineering software with robust security measures, such as anti-cheat systems.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend of mine gave me a binary virtualized with VMProtect3.8.1, configured with 100% complexity + 10vms. Although I’m an absolute novice in this field, I always wanted to know about virtualization technique I finally decided to tackle on it and write a diary about how I get wrecked! lol

In this blog post, I’ll share my observations and experiences during the analysis process. While it will be a comprehensive exploration of VMProtect’s features or an in-depth technical breakdown, as that’d be beyond my wheelhouse, it serves as an initial brief research. Consider it a beginner’s diary of grappling with advanced virtualization protection.

This article might be too rudimentary for those who ever dealt with VMProtect before. Also there might be misunderstandings, forgive me I’m not a professional.

Table of Contents

- About virtualization

- let’s get rekt!

- [+] Disable ASLR

- [+] The binary’s behavior

- [+] Main function

- [+] Confirm VM entry indication

- [+] Deadstore removal plugin

- [+] Locate vip initialization

- [+] Virtual stack initialization

- [+] Dissect VM handlers

- [+] Devirtualize it

- [+] Backward slicing RAX

- Conclusion

About virtualization

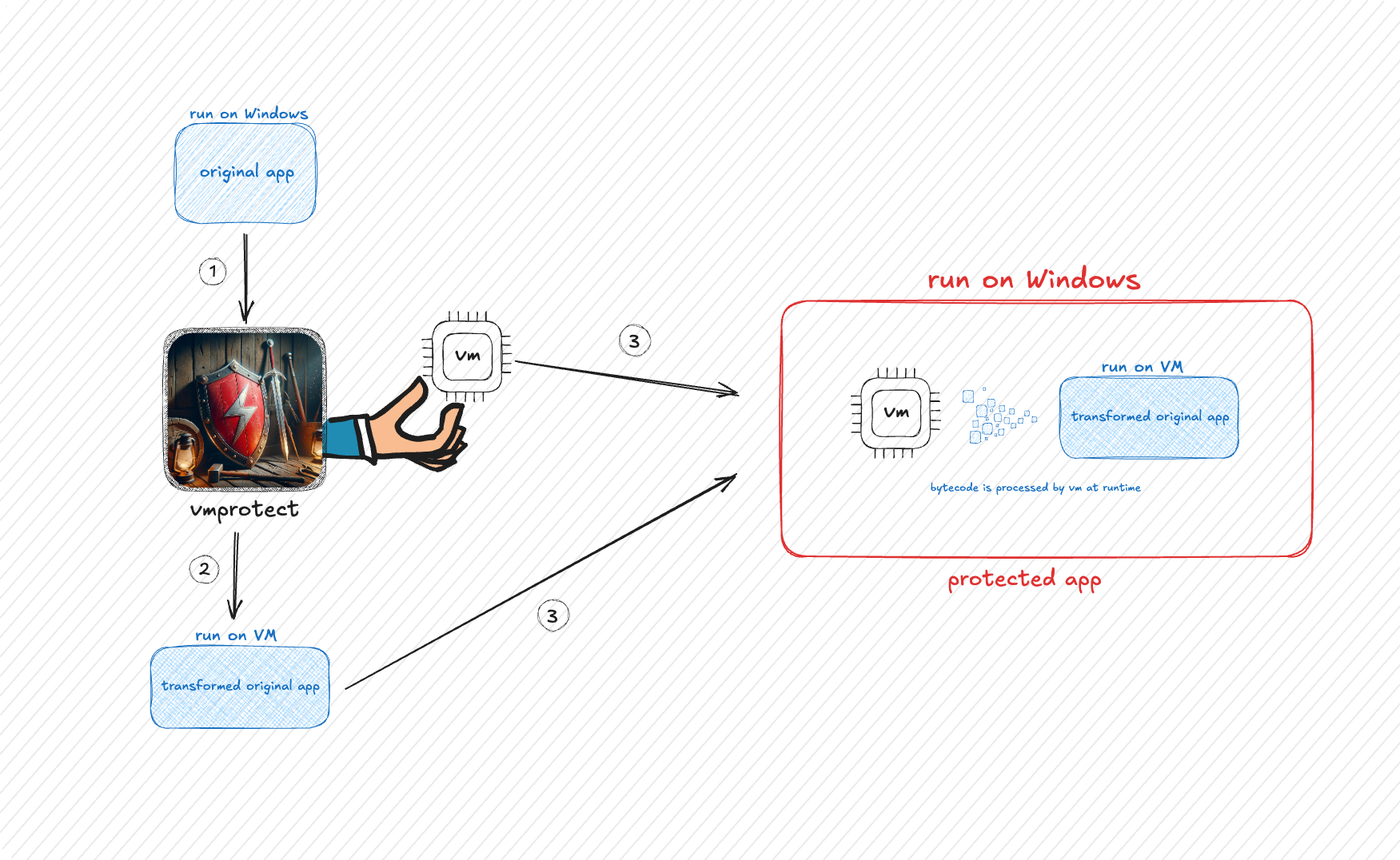

Virtualization is by far the strongest obfuscation done by transforming legit code into a custom bytecode that runs on a virtual machine (VM) embedded within the protected application. The virtual machine that runs in the application typically has a proprietary architecture that the static disassembler like IDA doesn’t recognize the bytecode(original code) as meaningful instructions and ended up with just showing a big chunk of bytes. I’ll show you the actual image of IDA’s disassembler view of it later.

Among a couple of softwares that have virtualization capabilities, this time I’ll take a look at a binary compromised with VMProtect version 3.8.1. VMProtect is an infamous software known for its strong protection techniques being developed by Russian firm, VMProtect Software. It applies not only virtualization to software but other obfuscation techniques such as deadstores insertion, opaque predicates, indirect jmp, stack manipulation…you name it!

VMProtect is a bin2bin1 type of obfuscator. It eats the original binary and spits out a new binary with a VM embedded in it. VMProtect has been updated frequently and considering the latest version as of now is 3.9, version 3.8.1 is pretty new I’d say.

Following figure is showing the brief overview of VMProtect.

So this was what you should know before diving into the actual contents!

Let’s get rect!

Upon writing this post, I had read a couple of papers and articles, also I peeked at VMProtect2 binary a bit before so I had a general idea of where to start. Moreover my friend told me where the VM begins, people call it VM entry, so that will also be a starting point.

But still, the binary is virtualized with 100% complexity, it could be more and more complicated than what I expect of course.

[+] Disable ASLR

I noticed that the binary was compiled with the /DYNAMICBASE option, which enables Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)2. This made debugging sessions unpleasant.

Fortunately, it’s relatively straightforward to disable this feature. Here’s how:

- Open the binary with your preferred hex editor.

- Navigate to the following location in the file structure:

NTHeader -> OptionalHeader -> DllCharacteristics -> IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_DYNAMIC_BASE - Set this value to 0.

Additionally, to ensure ASLR is completely disabled:

- Open Windows Settings and go to ‘Windows Security’.

- Navigate to the ‘App & browser control’ tab.

- Turn off the option ‘Randomize memory allocations (Bottom up ASLR)’.

By following these steps, you can disable ASLR and fix the image base across system reboots, which should significantly make your debugging process comfortable.

also setting

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Session Manager\kernel\MitigationOptions’s third significant bit to 0 does the same thing in registry.

[+] The binary’s behavior

Knowing what the binary does is the most important thing to know when you reverse enginer software so that you can presume for instance what kind of Windows API you would expect to be called or where to start. This particular one is a very simple VMProtect sample, so it was as straightforward as just print out number 2 and pop up a messagebox with a word “wait”.

it’s print out ‘2’ and pop up a message box

it’s print out ‘2’ and pop up a message box

[+] Main function

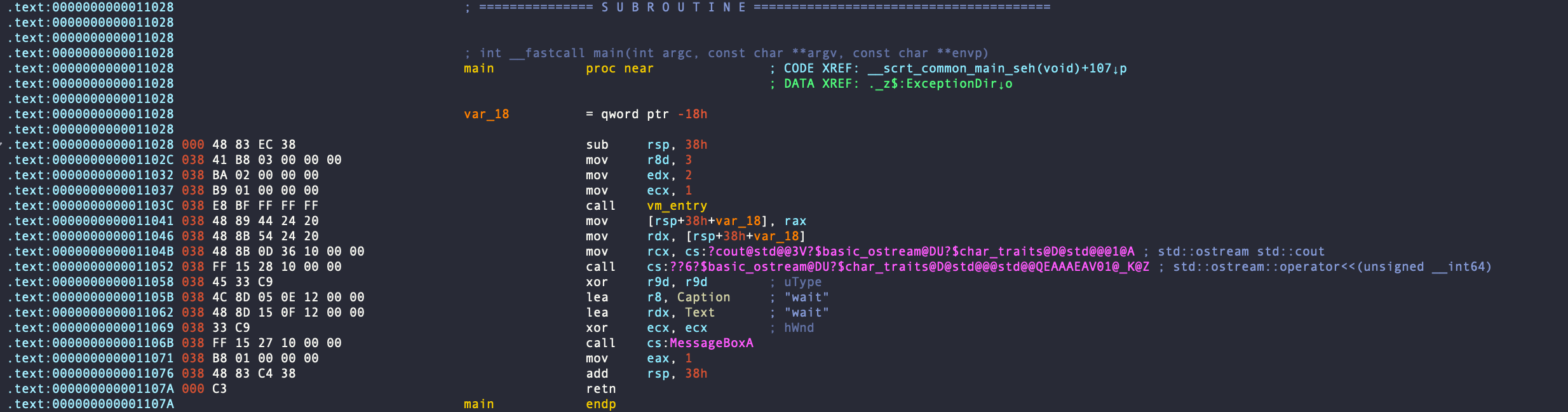

Right off the bat, look at the main function.

Subroutine marked as vm_entry is the virtualized subroutine. And it’s printing out the return value which I assume is 2.

Also just before entering vm_entry, the code assigning values to three registers and vm_entry is recieving the value as parameters.

1

2

3

mov r8d, 3

mov edx, 2

mov ecx, 1

[+] Confirm VM entry indication

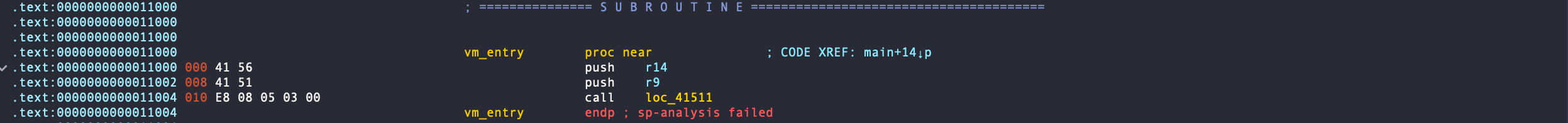

Now, let’s examine the VM entry (shown in the image below). As you can see, it’s pushing two registers before entering a subroutine. In VMProtect2, I recall that this operation typically involved pushing the encrypted vip (similar to rip, but in the VM context). However, I’m not certain if that’s the case here.

In this instance, r14 is set to 0, and r9 is holding a stack memory address that was initialized in the _initterm function. This doesn’t appear unusual to me at first glance. I’m unsure whether this is related to VMProtect’s operations or not.

Btw in the nature of VM entry, it should have a specific initialization process. Since it’s going to use general registers in its vm, it first push all the registers to stack to preserve the current state for later. Based on my experience of VMProtect2, I overconfidently thought ‘This should be easy’ and ended up learning a painful lesson.

In VMProtect3, the contents of VM entry were finely chopped up, and it seemed that a single operation was performed through multiple functions. In the VMProtect2 I had seen before, all register pushes were done in a single function, but this time even the pushes were divided into multiple functions and basic blocks, making it very difficult to search through

I eventually managed to find it, as I mentioned, it was all separated. The image below shows the largest piece of a function that pushes many general registers. The function has a branch in the middle; however, it turned out to be a part of the obfuscation technique known as opaque predicates3. (Virtualized subroutines contain numerous instances of these, by the way.) I’ve added comments to the picture explaining why it would always take the same branch.

red: opaque predicates, green: register push

red: opaque predicates, green: register push

[+] Deadstore removal plugin

By the way, the amount of deadstore VMProtect inserts between legit instructions are insane that I almost lose my temper so I quickly made an IDA plugin to remove all the deadstores in the current function.

Place it in IDA’s plugins folder. It’s utilizing a library called triton, therefore you have to build it to use my plugin. Also it works on IDA 8.X but doesnt work on IDA 9.X due to the API compatibility. You can use it by placing cursor on the middle of a function in IDA and run the plugin I named it “Function Deadstore remover”, so that the plugin will analyze and nop out every garbage instructions.

nop out deadstore, if the instruction made out of multipul bytes, it truncates them

nop out deadstore, if the instruction made out of multipul bytes, it truncates them

[+] Locate vip initialization

Many instructions in virtualized subroutines didn’t make sense to me, which was both confusing and frustrating. I wasn’t sure what to look for. However, one thing I knew was that VMProtect must have stored custom bytecode for the virtual machine somewhere in the binary. And wherever it was, the virtualized process would eventually have to access it.

So, I decided to debug the program and closely monitor the registers and stack to see if any of them started holding the bytecode pointer, usually referred to as vip (virtual instruction pointer). Basically during the execution, VM will assign address to the bytecode in one of the general registers (maybe stack too? not sure) to access values around it. It felt like it took ages to find it, but I finally made a breakthrough!

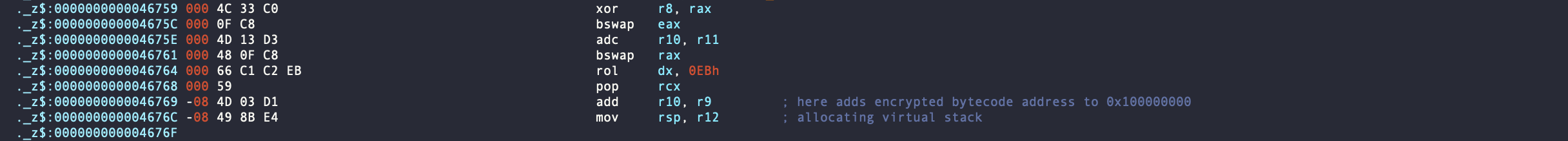

In the image below, you can see that r9 contains 0x100000000, and r10 holds the encrypted vip. As the program executed, r10 was decrypted along the way. By combining it with 0x100000000, the decryption process was completed, revealing the true vip.

1

0xFFFFFFFF0004114D + 0x100000000 = 0x04114D

virtual instruction pointer is being decrypted

virtual instruction pointer is being decrypted

And following is where the ptr was pointing to.

this is what VMProtect custom bytecode look like

this is what VMProtect custom bytecode look like

To confirm that I had indeed found the correct pointer, I continued debugging and looked for instructions that used r10. Eventually, I found the part where it retrieves a byte from vip-7 and moves the vip forward. It appears that vip is updated by subtracting the number of bytes it has already referenced after a certain number of references.

getting a byte from vip and updating pointer

getting a byte from vip and updating pointer

Note that vip looks technically going backward just like stack does, but apparently it varies depending on the vm you’re dealing with. Some vms actually go forward and others go backward.

[+] Virtual stack initialization

Apparently, to avoid contaminating the existing stack, the VM allocates an exclusive stack frame.

Here it seems allocating new stack frame for vm.

Moving r12 to rsp, r12 is pointing to another stack memory, and the gap between r12 and rsp is 0x260. By doing this it’s creating exclusive stack of size 0x260 while preserving current stack at the same time.

As per an articles I’ve read before, within this 0x260 there’re a part for what’s called Virtual registers and Virtual stack respectively. Apparently it treats them differently for registers and stack but since I didn’t recognize its difference during this analysis well, I won’t mention about it lol.

Moving on.

[+] Dissect a VM handler

So far, we’ve looked at several VM initialization processes, but most virtualized functions consist of many VM handlers. I think each VM handlers are equivalent to x64 assembly instructions like mov, add, xor, inc, and so on. However, because VMs have their own architecture, unlike normal instructions, each instruction becomes a very large block of code. Here, I’ve taken relatively simpler VM handler as a sample, and I’d like to examine it in detail.

This represents one unit of a VM handler. I deliberately included the obfuscated version to show readers the actual disassembly. They should semantically be a single routine, though it’s been chopped up into numerous basic blocks.

Let’s closely look at them!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

0000000000044792 mov eax, 21322628h

0000000000044797 neg rax

000000000004479A mov r11, [rbx+rax*2+42644C50h]

00000000000447A2 lea r8, [rsp+rax*2+42644D10h]

00000000000447AA movzx r9d, al

00000000000447AE lea rbp, [rax+rax+750119A6h]

00000000000447B6 mov [rax+r8+21322628h], r11

00000000000447BE lea r8, ds:0FFFFFFFF9E3824A7h[rbp*2]

00000000000447C6 mov rbp, [rbx+rax*2+42644C58h]

00000000000447CE jge loc_C2AF1

00000000000447D4 movsx r11d, r8w

00000000000447D8 lea rcx, [rsp+rax*2+42644C60h]

00000000000447E0 mov [rcx+rax+21322628h], rbp

00000000000447E8 call sub_8695C

000000000008695C mov r11, [rax+r10+21322620h] ; r11 = (QWORD*)((char*)vip - 8)

0000000000086964 movzx ebp, ax

0000000000086967 xor r11, rdi

000000000008696A rol r11, 1

000000000008696D push rax

000000000008696E neg [rsp+rax*2+8+arg_42644C43]

0000000000086976 mov [rsp+r9*2+8+var_1B8], 0B9884282h

0000000000086982 not r11

0000000000086985 lea r8, ds:0FFFFFFFFEABD1E31h[r9*4]

000000000008698D sal ebp, 78h

0000000000086990 call sub_83C34

0000000000083C34 bswap r11

0000000000083C37 xadd bp, ax

0000000000083C3B rol r11, 2

0000000000083C3F neg r11

0000000000083C42 mov ecx, r8d

0000000000083C45 rol rbp, cl

0000000000083C48 xor rdi, r11

0000000000083C4B mov [rsp+rax*2+arg_42660008], 0CBD428Eh

0000000000083C57 mov [rbx+rax*2+42660008h], r11

0000000000083C5F movsx r11d, al

0000000000083C63 dec ebp

0000000000083C65 pop r9

0000000000083C67 movzx r8d, byte ptr [r10+rax+2132FFF7h] ; r8d = (BYTE*)((char*)vip - 9)

0000000000083C70 xor [rsp+r11*8-8+arg_2], r11d

0000000000083C75 jnb loc_CBAC0

00000000000CBAC0 xor r8b, dil

00000000000CBAC3 inc rbp

00000000000CBAC6 dec r8b

00000000000CBAC9 call sub_9DCE3

000000000009DCE3 xor r11b, cl

000000000009DCE6 call sub_84C20

0000000000084C20 ror r8b, 1

0000000000084C23 mov r9d, 3C8CAD36h

0000000000084C29 mov edx, 3703F011h

0000000000084C2E not r8b

0000000000084C31 rol r8b, 1

0000000000084C34 dec bpl

0000000000084C37 setp cl

0000000000084C3A pop rcx ; rcx gets return address on top of the stack

0000000000084C3B add rcx, 4ABEh ; add constant offset to it

0000000000084C42 jmp rcx ; jmp

00000000000A27A9 xor dil, r8b

00000000000A27AC lea r8, [rsp+r8+arg_10]

00000000000A27B1 mov rdx, [r8+rax+21330000h]

00000000000A27B9 pop rax ; rax gets return address 0xCBACE

00000000000A27BA add rax, 0FFFFFFFFFFFBE97Eh ; add constant offset to it

00000000000A27C0 jmp rax ; jmp

000000000008A44C lea r8, [r11+r9-5DDEB1F0h]

000000000008A454 mov [rbx+r11*2-122h], rdx

000000000008A45C and r8w, [rsp+r11-88h]

000000000008A465 call sub_B0A97

00000000000B0A97 rol [rsp+r11*2+var_116], 0ACh

00000000000B0AA1 mov eax, [r11+r10-9Eh] ; rax = (DWORD*)((char*)vip - 13)

00000000000B0AA9 lea rcx, ds:0FFFFFFFFFD9592B7h[r8*4]

00000000000B0AB1 ror r8w, 24h

00000000000B0AB6 shr r9w, 0C4h

00000000000B0ABB lea r10, [r10+r11*2-12Fh] ; vip is no longer used in this VM handler, thus it moves pointer forward by 13

00000000000B0AC3 xor eax, edi ; rax decryption starts by xoring with rolling key (edi)

00000000000B0AC5 movzx edx, r11w

00000000000B0AC9 shr r11, 44h

00000000000B0ACD xor r8b, [rsp+r11+arg_3]

00000000000B0AD2 inc eax ; rax decryption

00000000000B0AD4 ror eax, 1 ; rax decryption

00000000000B0AD6 xor eax, 8F8E1812h ; rax decryption

00000000000B0ADB or bp, r8w

00000000000B0ADF not eax ; rax decryption

00000000000B0AE1 mov [rsp+r11+7], rdi

00000000000B0AE6 xadd dl, r8b

00000000000B0AEA push r9

00000000000B0AEC xor [rsp+r11*2+6], eax

00000000000B0AF1 mov rdi, [rsp+r11+0Fh]

00000000000B0AF6 mov [rsp+r9+8+var_3C8C0AD3], rcx

00000000000B0AFE xor ebp, 0BDB8BB35h

00000000000B0B04 movsxd rax, eax

00000000000B0B07 jge loc_46A00

0000000000046A00 pop r9

0000000000046A02 adc rsi, rax ; add rax + carry flag to rsi which calculates final rsi

0000000000046A05 and [rsp+rbp*2+var_1C112186], dl

0000000000046A0C mov r11, [rbx+rbp*8-70448650h]

0000000000046A14 mov rax, [rbx+rbp*2-1C11218Ch]

0000000000046A1C pop r9

0000000000046A1E adc r11, rax

0000000000046A21 add [rsp+r8-8+arg_2152D471], r9b

0000000000046A29 lea rbp, ds:0FFFFFFFFDB094088h[r8*4]

0000000000046A31 mov [rbx+r8+2152D477h], r11

0000000000046A39 lea rbx, [rdx+rbx-1Dh]

0000000000046A3E mov [rsp+r8-8+arg_2152D477], 733392B5h

0000000000046A4A neg bp

0000000000046A4D mov [rsp+r8*2-8+arg_42A5A8DE], rsi ;rsi holds next VM handler address

0000000000046A55 retn 8

1. Eye catching characteristics

As you can see, this code employs numerous disruptive techniques to obfuscate its components.

Firstly, each memory access involves addition or subtraction operations with registers and constants to obscure offsets from static analysis. This approach makes it challenging to predict exactly where the code is accessing memory. Moreover, it complicates the process of searching for specific disassembly by looking for byte sequences. Instead you have to code small tool with disassembler to find them I would say. Fortunately, despite the large constants used, the results of these calculations are usually simple.

1

2

3

4

lea rbp, [rax+rax+750119A6h]

mov [rax+r8+21322628h], r11

lea r8, ds:0FFFFFFFF9E3824A7h[rbp*2]

mov rbp, [rbx+rax*2+42644C58h]

Secondly, the code exits the current subroutine as soon as it encounters a call or jmp instruction. Regardless of the subroutine’s size, once it hits a call or jmp, it continues execution at another location, abandoning the rest of the current subroutine and never returning to where it left off.

The image below illustrates how VM jumps around the text section. The parts with yellow background is where it actually executed, and the rest of them are not in entire execution.

execution flow is obscured by jumping around

execution flow is obscured by jumping around

Lastly, the code frequently uses indirect jumps with general registers such as rax, rcx, r9 and so on. A register to jump seems randomly selected for each jump. However, there’s a unique pattern: the jump destination is always calculated by adding a constant to the return address pushed onto the top of the stack from the last call instruction.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

pop rax ; rax gets return address 0xCBACE

add rax, 0FFFFFFFFFFFBE97Eh ; add constant offset to it

jmp rax ; jmp

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

pop rcx ; rcx gets return address on top of the stack

add rcx, 4ABEh ; add constant offset to it

jmp rcx ; jmp

2. Opcode and operand

In previous section, I mentioned that opcodes and operands that VM utilizes are embeded as bytecode, and vip is holding current position of bytecode. Since we already discovered that r10 is vip, let’s follow how r10 is used, shall we?

Firstly a qword size value was extracted usingr10 and assined to r11. The following is the all instructions involves r11. I’ll explain it line by line

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

mov r11, [rax+r10+21322620h] ; load QWORD value from ((char*)vip - 8)

xor r11, rdi ; decryption starts

rol r11, 1 ; decryption

not r11 ; decryption

bswap r11 ; decryption

rol r11, 2 ; decryption

neg r11 ; decryption

xor rdi, r11 ; rolling decryption key update

mov [rbx+rax*2+42660008h], r11

Look at this decryption routine closely. In this VM, the rdi register plays a crucial role as the rolling decryption key. The values embedded in the bytecode field are self-encrypted. Therefore extracted value using vip always gets decrypted, and the rolling decryption key is responsible for initiating the first step in a series of decryption procedures. A consistent pattern throughout VM is that once a decryption operation is completed, the rolling decryption key is updated as well using the newly extracted value.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

xor r11, rdi ; decryption starts

rol r11, 1 ; decryption

not r11 ; decryption

bswap r11 ; decryption

rol r11, 2 ; decryption

neg r11 ; decryption

xor rdi, r11 ; rolling decryption key update

In the last line, the result of [rbx+rax*2+42660008h] points to a stack memory. And at that moment r11 holds 0. So at the end of the day it’s basically zeroing out a specific stack memory. At first glance, this operation may seem meaningless when viewed in isolation. However, this is actually initializing memory to zero, which will be used to store important calculation results that appear in the next ‘Devirtualize it’ section.

1

mov [rbx+rax*2+42660008h], r11

Secondly, r10 is used here. The first 7 lines are same as previous one.

And it’s hard to read because of the obfuscation but in last 4 lines, it’s assigning some random value to the stack memory zeroed out last operation and load its address to rbx.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

movzx r8d, byte ptr [r10+rax+2132FFF7h] ; load BYTE value from ((char*)vip - 9)

xor r8b, dil ; decryption starts

dec r8b ; decryption

ror r8b, 1 ; decryption

not r8b ; decryption

rol r8b, 1 ; decryption

xor dil, r8b ; rolling decryption key update

lea r8, [rsp+r8+arg_10]

mov rdx, [r8+rax+21330000h]

mov [rbx+r11*2-122h], rdx

lea rbx, [rdx+rbx-1Dh]

3. Calculating next VM handler address

When finishing the current VM handler and moving on to the next one, the code consistently uses the rsi register with a ret instruction. This led me to investigate the source of rsi’s value.

The final step before jumping to the next handler looks like this:

1

2

3

; [rsp+r8*2-8+arg_42A5A8DE] is equivalent to [rsp].

mov [rsp+r8*2-8+arg_42A5A8DE], rsi

retn 8

Tracing back, I found that rsi is calculated by combining it with rax and the carry flag. At this point I thought rax is most likely an relative offset to the next VM handler.

1

2

; add rax + carry flag which calculates final rsi value

adc rsi, rax

To understand this fully, I needed to trace rax’s initialization and subsequent mutations. There are six key instructions involving rax:

1

2

3

4

5

6

mov eax, [r11+r10-9Eh] ; load DWORD value from ((char*)vip - 13)

xor eax, edi ; decryption

inc eax ; decryption

ror eax, 1 ; decryption

xor eax, 8F8E1812h ; decryption

not eax ; decryption

The initial value of eax is loaded from 13 bytes before the current vip (virtual instruction pointer). The image below is the actual value in my sample around vip. So in first instruction 0x5F17544C is assigned to eax, it then goes through a series of decryption steps as shown above and consequently becomes 0x5ecd6741. An interesting fact is that only when VM handler calculates next handler’s offset, it doesn’t decrypt rolling key. I confirmed it in every handlers.

This process reveals that the offset to the next VM handler is embedded near the vip. The virtualized function extracts and decrypts this value each time to calculate the offset to the next handler. This mechanism makes it challenging to statically analyze the code flow, as the next handler’s location is dynamically determined at runtime.

4. Updating vip

At last, r10 gets updated according to the bytes that were used in this handler. Following is where r10 is updated for use in the next VM handler.

1

2

; r11*2-12Fh is -13

lea r10, [r10+r11*2-12Fh]

Up to this point, the VM has consumed 13 bytes from the memory region pointed to by r10.

- 8 bytes for operation

- 1 byte for operation

- 4 bytes for offset to the next vm handler

The calculation r11*2-12Fh results in -13, which precisely subtracts the number of bytes used in the current VM handler.

Some ginormous VM handlers actually update its

vipmultiple times within a handler.

[+] Devirtualize it

To further investigate the virtualized code, I needed to know the overview of what exactly it’s doing. Luckly I have a tool to devirtualize the code.

To clarify, when I say ‘devirtualize’ here, it means to lift the code into LLVM IR4 to better understand what the virtualized subroutine does.

For this devirtualization process, I used NaC-L/Mergen, which is an impressive tool designed to disassemble obfuscated binaries and lift them into deobfuscated LLVM IR through optimization. Mergen’s approach allows it to handle not just VMProtect, but a wide range of obfuscators and virtualizers, making it a versatile solution for this kind of work.

I found it so cool that I made a couple of small pull requests to contribute it! You have to check it out too!

Following is the lifted LLVM IR

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

; ModuleID = 'my_lifting_module'

source_filename = "my_lifting_module"

; Function Attrs: mustprogress nofree norecurse nosync nounwind willreturn memory(argmem: write)

define i64 @main(i64 %rax, i64 %rcx, i64 %rdx, i64 %rbx, i64 %rsp, i64 %rbp, i64 %rsi, i64 %rdi, i64 %r8, i64 %r9, i64 %r10, i64 %r11, i64 %r12, i64 %r13, i64 %r14, i64 %r15, ptr nocapture readnone %TEB, ptr nocapture writeonly %memory) local_unnamed_addr #0 {

entry:

%GEPSTORE-5368971276-4154 = inttoptr i64 1376064 to ptr

store i64 %r8, ptr %GEPSTORE-5368971276-4154, align 4

%GEPSTORE-5368930894-4155 = inttoptr i64 1376056 to ptr

store i64 %rdx, ptr %GEPSTORE-5368930894-4155, align 4

%GEPSTORE-5369500900-4156 = inttoptr i64 1376048 to ptr

store i64 %rcx, ptr %GEPSTORE-5369500900-4156, align 4

%realnot-5369329545- = sub i64 %rcx, %rdx

%adc-temp-5369316182- = add i64 %realnot-5369329545-, %r8

ret i64 %adc-temp-5369316182-

}

attributes #0 = { mustprogress nofree norecurse nosync nounwind willreturn memory(argmem: write) }

As you can see it’s basically performing rcx - rdx + r8 and returning the result. These registers look familiar because they’re the ones initialized just before entering vm_entry.

To recap, their values are:

rcx: 1rdx: 2r8: 3

respectively.

Plugging these values into the equation, we get:

1

1 - 2 + 3 = 2

Therefore, we can conclude that the virtualized subroutine is ultimately returning the value 2.

I know what you thinking. “Why would you be suffered from reversing virtualized code when you can devirtualize it with a tool?” It’s because I don’t want to be a dumb that’s using tools blindly without thinking.

[+] Backward slicing RAX

So far, I reversed a couple of VM handlers but didn’t fully grasp their purpose.

However now I know the way to examine a VM handler that might reveal its functionality more clearly. Here’s my approach:

I know the virtualized subroutine performs the calculation 1 - 2 + 3 somewhere within it and returns the result. This means that rax should hold the result value, 2, just before exiting the virtualized subroutine. I reasoned that tracing rax backwards would lead me to the VM handler responsible for the arithmetic operation.

Following is the tracing log showing the transition between virtualized subroutine and main.

tracing log between virtualized and non-virtualized

tracing log between virtualized and non-virtualized

We can see that the value inside rax was popped from the stack at the end. I traced it back to where it was originally calculated, which turned out to be a hell of a long journey. This was because VMProtect meaninglessly transferred the post-calculation value of 2 between the stack and registers multiple times.

Eventually, I found the location of the final calculation, which is -1 + 3:

performing core arithmetic operation

performing core arithmetic operation

It’s worth noting that the values in rdx (-1) and r8 (3) were calculated in advance by other VM handlers. However, I’ll refrain from extending this blog post with more obvious details. For now, I’ll conclude my analysis here!

Conclusion

Throughout this research, I’ve uncovered some interesting techniques and tendencies in VMProtect’s virtualization process. While I’ve gained a basic understanding of what’s happening in these virtualized routines, more advanced tasks like patching and hooking virtualized functions, or recompiling to a fully devirtualized binary, remain significant challenges that I’ll need to tackle in the future.

But thanks to this research I’m pretty sure I’ll be capable of it one day.

References

Zakocs, M. (2021) Title, Mitchell Zakocs. Available at: https://www.mitchellzakocs.com/blog/vmprotect3

IDONTCODE (2021) VMPROTECT 2 - detailed analysis of the Virtual Machine Architecture, Private Group Of Back Engineers. Available at: https://blog.back.engineering/17/05/2021/

Footnotes

bin2bin: a type of obfuscation software. stands for binary to binary. There’s another type linker level obfuscation according to es3n1n’s Blog. ↩︎

ASLR: Address Space Layout Randomization. When it is enabled, the binary will be loaded at random location each time which means you have to rebase the program in IDA everytime open it with x64dbg. ↩︎

Opaque predicates: a type of obfuscation techniques which generates a seemingly legit branches that is actually a garbage branching taking you the same branch every time. ↩︎

LLVM IR: LLVM’s intermediate representation. ↩︎